By Robert Perry

When most people think of climate change, they focus on the atmosphere. In truth, it is our oceans, lakes and other water resources that serve as the bulwark in preserving a livable climate and are closer to collapse than most realize. Indeed, acceleration of climate change will reach a whole new level when our oceans and lakes reach a saturation point and cease to absorb carbon from the atmosphere.

We at the World Business Academy are dedicated to finding solutions and one motto often invoked is “Think Globally, Act Locally.” While this maxim delivers an indisputable truth, it is usually executed in the opposite direction: i.e., an effective local action is replicated and can spread outward to the entire globe. It is in this spirit that the following images and narrative are offered to describe how we can repurpose the oil platforms off our coast as a local pilot project for a much more ambitious global undertaking in the Gulf of Mexico and beyond.

Background and History of Offshore Oil Production

Discovery of oil off the coast of California dates back to the early European explorers who noted oil slicks in the Santa Barbara channel. In 1792, when the English explorer James Cook anchored his ship in the Santa Barbara Channel, his navigator George Vancouver wrote that the sea was “… covered with a thick, slimy substance,” and added “… the sea had the appearance of dissolved tar floating on its surface, which covered the ocean in all directions within the limits of our view.”

Offshore drilling began here in 1896, when operators in the Summerland Oil Field followed the field into the ocean by drilling from piers built out over the ocean, and at least 187 offshore oil wells were drilled by 1902. In 1947, the US Supreme Court ruled that the federal government owned all the seabed off the California coast. However, Congress passed the Outer Continental Shelf Act in 1953, which recognized state ownership of the seabed within 3 nautical miles (6 km) of the shore.

The United States controls the issuance of new oil and gas leases in federal waters. While the state of California does not control that land, it has repeatedly objected to allowing new leases in adjacent federal waters and the federal government, through the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, has not issued new leases in California coastal waters for over twenty years.

The Decommissioning Process

Decommissioning is the process of ending offshore oil and gas operations at an offshore platform and returning the ocean and seafloor to its pre-lease condition. This process is incredibly expensive and several sources estimate that current decommissioning costs for total removal of all offshore production facilities and pipelines in the Gulf of Mexico are between $38–$40 billion and the estimated cost to decommission the 23 platforms residing in federal waters off California is approximately $1.5 billion in 2014 dollars, with costs increasing over 10% each year, and only if the platforms are removed in groups, not individually. Clearly, this is money that could be better utilized by repurposing the platforms and pipelines to advance renewable energy and marine decarbonization technologies.

The Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act (OCSLA) and underlying regulations typically require the operator to remove seafloor obstructions, such as offshore platforms, within one year of lease termination, or prior to termination of the lease if the structure is deemed unsafe, obsolete, or no longer useful. Decommissioning an offshore platform generally entails:

- Plugging all wells supported by the platform and severing the well casings 15 feet below the mudline;

- Cleaning and removing all production and pipeline risers supported by the platform;

- Removing the platform from its foundation by severing all bottom-founded components at least 15 feet below the mudline;

- Disposing the platform in a scrap yard or fabrication yard, or placing the platform at an artificial reef site; and

- Performing site clearance verification at the platform location to ensure that no debris or potential obstructions to other users of the OCS remain.

Local Action in the Santa Barbara Channel

There are four offshore oil platforms in state waters, including Platform Holly, and 23 platforms in federal waters located off the California coastline. Below, the seven platforms shown below in red have been retired and are scheduled for decommissioning. These platform locations span the length of the Santa Barbara Channel and offer a variety of repurposed uses both above and below the water line. Below are just a few potential repurposed uses for these platforms:

Offshore Wind and Wave Energy: Located off Points Arguello and Conception, Platforms Hidalgo, Harvest and Hermosa offer offshore wind capacity that can bring diversity to Santa Barbara’s solar capacity. For example, Steve Weaver of Weaver & Associates has developed a proposal to convert Platform Hermosa into a central anchor point for a floating offshore wind farm that would interconnect to a substation at Gaviota. The proposal estimates that up to 100MW of energy could be generated by such a facility.

Research, Education and Eco-Tourism: Located close to land, Platform Holly would be ideal to serve as a marine research and educational facility offering a broad curriculum to local schools and universities of all levels. Another complementary use could be as an eco-resort catering to tourists interested in scuba diving and aquaculture. Under these circumstances, the platform’s current industrial structure would be stripped away and replaced by a functional but aesthetically appealing architecture that could extend down to, and even below, the water line. Imagine classrooms, conference facilities or hotel suites offering an underwater view of the abundant and diverse marine life!

Marine Aquaculture / Eco-System Restoration. In all locations, the lattice structure of the platforms plays host to an abundance of marine life and could be used to develop aquaculture ecosystems that help clean and maintain seawater quality. Dr. John Todd of John Todd Ecological Design and Ocean Arks International, together with his wife Nancy and son Jonathan (who also operates Eco Lake Solutions), has spent the past 50 years developing wastewater treatment and ecological remediation projects that “use biodiversity and natural processes to create mechanically simple but biologically complex systems capable of treating the most difficult contaminants and human waste streams.” The Todds believe that their twelve principles of ecological design can be adapted to cleanse polluted, acidic and oxygen deprived marine environments using halophytic (saltwater tolerant) plants such as kelp and seaweed. These types of systems, distributed globally, could serve to significantly restore Earth’s oceans to their previous vibrancy.

Replication and Expansion in the Gulf Coast

While California has withstood attempts to increase offshore oil production, the Gulf of Mexico has become one of the largest offshore petroleum regions in the world, comprising one-sixth of the United States’ total production. The size of the Gulf basin is approximately 615,000 square miles, with almost half of the basin in shallow continental shelf waters. As of April 2019, there are approximately 1,862 platforms in the Gulf of Mexico. As of January 1, 2017, 515 platforms have been converted to permanent artificial reefs in the Gulf of Mexico. Clearly, many of the platforms (orange dots) would need to be converted to reefs, but many others could be repurposed for renewable energy and other productive purposes connected to the mainland via conduit run through pipelines (in green).

The fragile state of the Gulf was brought into public focus by the 2010 Deepwater Horizon spill, where crude oil gushed from the spewing wellhead over 86 days, spilling 4.9 million barrels of oil followed by an additional 1.84 million gallons of toxic dispersants, making it the most toxic marine event ever. Combined with nutrient runoff from the Mississippi River watershed, man-made pollutants have created a dead zone of oxygen-depleted waters that forms every summer. Scientists determined that this area in 2019 encompassed approximately 6,952 square miles, the 8th largest dead zone ever recorded.

Environmental damage will accumulate as long as these destructive activities persist and repairing this damaged environment will require an effort of “Green New Deal” scale. Applying lessons learned in the Santa Barbara Channel would require upscaling on an exponential scale, but the need is also exponentially greater, and the massive infrastructure shown above could be repurposed to breathe life back into what was once one of the most biodiverse and productive regions on the planet.

The Global Solution

Of course, there are many other areas on the planet that must be repaired and restored. As of May 2015, there were 1,470 offshore oil rigs located around the world. The chart below, based on data from Statista, shows the areas where they are located. These oil rigs are floating and could be repositioned as needed to address the various environmental “hotspots” in need of remediation.

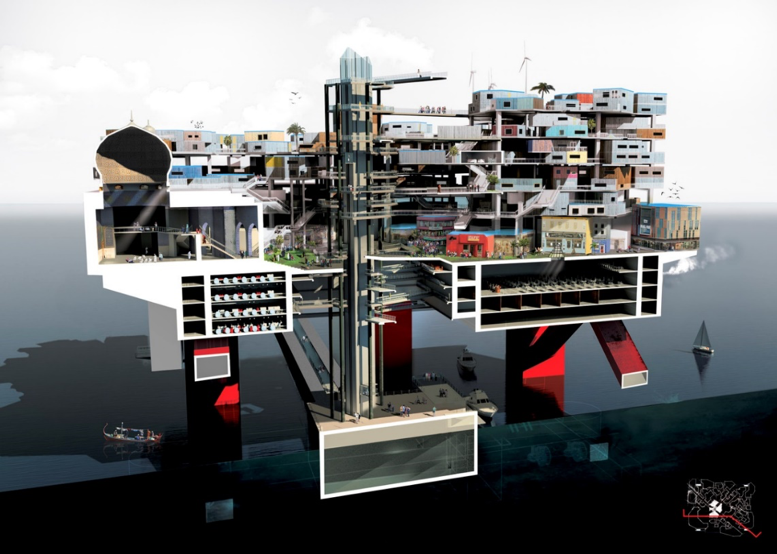

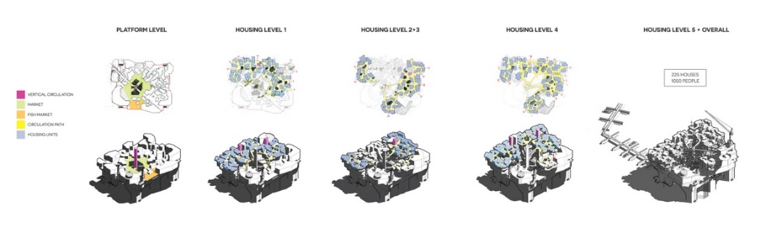

Last but never least, a strategy will be needed to create homes for those displaced by climate change effects in low-lying areas. For example, consider the master thesis of architect Mayank Thammalla from the Unitec School of Architecture in Auckland, New Zealand. Thammalla’s research project seeks to preserve Maldivian life in the same geographical location as it is now through repurposing semi-submersible oil rigs. In his Tedx video, Thammalla estimates that each repurposed rig could house over a 1,000 people!

With every new study and analysis, the threat of climate change accelerates and comes closer to disastrously impacting humanity. We simply do not have the time to both dismantle existing infrastructure and build entire new systems to slow and reverse climate change. An agile strategy will require examining all tools at our disposal, even including the ones that created the problem, and I cannot think of a more fitting means of addressing climate change than to convert offshore oil and gas infrastructure into a regenerative system of carbon sequestration and environmental remediation.

This is but one area where infrastructure repurposing can be used to mitigate and adapt to climate change, and we will need more innovative thinking like that of John Todd, Steve Weaver and Mayank Thammalla to right the listing ship of Planet Earth. Look around and ask yourself: how we can change what we have built to help create a clean, new world?